Mosman Parks & Bushland Association 1964-2014.

A talk given by Ann Cook, a committee member of the Mosman Parks & Bushland Association, to the Mosman Historical Society in September 2014.

It covers a short history of Eileen and Joan Bradley (the Bradley Sisters) and their development of a method bush regeneration and the formation of the Ashton Park Association which developed into Mosman Parklands and Ashton Park Association and then into the Mosman Parks & Bushland Association.

Good evening everyone – I want to pay my respects firstly to the Borogegy people, custodians of this land until the late C18th, whose collective wisdom based on 1000s of years’ experience of their environment has sadly been lost to history. And, I thank the Mosman Parks & Bushland Association, and Elizabeth Elenius and Ann Bowe, nieces of the Bradley sisters, for access to their invaluable archives

I researched and wrote a long essay on the origins and development of bush regeneration about 12 years ago. I found that to research ‘origins’ is a bit like jumping into a pool and never touching the bottom. So I could take you back to 1066 and the arrival in England of William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy. Among the conquerors was William de Bourton, the Burton Bradley family’s distant ancestor. But we have not got time. Suffice it to say that that was the founding of a distinguished British family of nature lovers. In the first half of the nineteenth century a branch of that family was established in the colony of NSW, and it produced several fine naturalists and gardeners and even a pioneer geneticist in the early C20th. A fascinating story in itself. Moving closer to the present I can see that those great gardeners, naturalists and eco-pioneers, the Bradley sisters, knew about the work of Albert Morris of Broken Hill, who realised that the city’s terrible problems with dust storms were the result of the denudation of the earth in and around the town. And they were certainly familiar with the work of PA Yeomans who developed the Keyline plan to manage water on farms and understood the role that vegetation plays in hydrology and was an early advocate of planting trees.

But I will start this talk by tracing the story through the archives of the Mosman Parks & Bushland Association under the auspices of which the Bradley sisters developed their

original insight, that bushland can regenerate itself …. once freed from the competition of non- native flora, or, weeds.

Their definition of a weed is a plant out of place, and I don’t think it has been bettered.

The story begins in the mid1960s in Ashton Park, now part of Sydney Harbour National Park, at Bradleys Head (which, incidentally, was named after Lieutenant William Bradley of the first fleet, no relation to our Bradleys it seems).

Ashton Park was gazetted in 1908 amid widespread public concern about the alienation of land around the harbour. It was dedicated for Public Recreation in 1918. One conservationist of those days compared the future of Sydney Harbour to that of a pond in a privately owned and guarded paddock. According to a prior agreement the Zoological Society was granted part of Ashton Park and in 1914 the animals were progressively transported from Moore Park across the Harbour as their new homes – some might say prisons - became available. There is something very poignant about the image of Jessie the Indian elephant standing steady as a rock on a barge in the middle of Sydney Harbour.

By the 1950s the boards of The Ashton Park Trust and neighbouring Taronga Zoological Park Trust were identical, with the wealthy philanthropist Sir Edward Hallstrom and then his son John serving as chair of both boards. As the designer and fabricator of Silent Knight fridges Hallstrom enjoyed hero status among Sydney housewives and the government liked him too because of the large amounts of his own money he spent as Honorary Director of Taronga Park Zoo. It was clear that the bushland of Ashton Park was regarded as a resource for the zoo: as extra acreage when required, as a source of plant material for the animals, as a dumping ground and as a quarry. The advent of the great age of the motor-car made it look very valuable as potential car-parking space as well. One director was heard to comment publicly on the zoo’s good fortune in having all that land at its disposal, Hallstrom the Elder was literally one-eyed, having lost the sight in the other when a giraffe sat down on him at the Melbourne Zoo.

So the well-being of the lovely wooded headland, which from the water and the opposite shore still appeared very much to retain its pre 1788 aspect, was in the hands of one individual whose wealth and generosity had apparently absolved him of accountability, at least in the estimation of the state Department of Lands and Mines whose business it then was to oversee the administration of public parks and reserves.

In February 1964, while traveling home to Mosman from the city by ferry Dr Helen Maguire, a scientist at Sydney University, looked towards Bradleys Head and was appalled to see a bulldozer tearing into the bush there. Her horror was shared by others. With no notice to the Council or the residents The Ashton Park Trust had authorized the destruction of the bush and the construction of a road through the park to the waters’ edge, a road from nowhere to nowhere some said. It was suggested that it was simply so the Trust could charge an entry fee that the road was built. A very public furore erupted in the local and greater metropolitan press as Helen Maguire, Edward St John, Colman Wall, Frank Hutley, the Bradleys, June Gram and other locals recruited friends and relations from inside and outside the district to lobby the state government.

Deputations of very cross people went into the city to call on the Premier and the Minister and a public meeting was called in Mosman chaired by Edward St John.

A local alderman told the meeting that The Taronga Park Trust had a schizophrenic personality with conflict of interest resolved in favour of hippopotami. Ashton Park on the other hand was characterized as a foundling on the doorstep of the city, unloved by its parents and unnourished by government. It was further revealed that the baby had not only been neglected but also abused, with pieces having been hacked off and given away. At the meeting it was decided that The Ashton Park Association be formed, the objectives of which would be to prevent further encroachment on the park to restore as much as possible of the originally dedicated area and to preserve the park for public recreation and enjoyment with as much bushland as possible.

At the new resident action group’s AGM in July 1964 the members were warned Taronga Park could swallow Ashton at a gulp, an inspired zoological image, used earlier on a flier for a letterboxing campaign: one thinks of a boa constrictor swallowing a little possum.

Because of the roadway fiasco in 1964 Mosman Council decided that it needed representation on the The Ashton Park Trust and in 1965 two aldermen were appointed to the Trust.

In 1966 the Ashton Park Trust produced a Master Plan for the development of Ashton Park. This plan if effected would have greatly added to the zoo’s resources, turning a lot of the Ashton Park bushland into a parking area, a visitors’ centre, superintendent’s residence and a large terraced seating area.

The Association responded to the Master Plan with their own document A Critical Evaluation of the Master Plan co-authored by Joan Bradley and June Gram. The conservationists felt that the development proposal violated three important principles of land-use - the social, the aesthetic and the physical, and that the … gross interference with the natural environment … would have destroyed its future as an example of the original environment of Port Jackson.

Responding to the Master Plan the Association wanted to take a positive line where possible and did note that on the plus side the Trust had for the first time made its plans public before executing them, and that it had attempted to address issues of weed infestation and soil erosion. The authors also offered an alternative plan, in which they proposed that three questions should be asked of any proposal for development in Ashton Park:

Will it fit into the pattern of public use, adding to the pleasure which the park gives its visitors, or at worst cause no serious inconvenience? Will it look well, or if unavoidably unsightly, be well-concealed? Will it benefit the bush, or at worst cause no harm to it?

The order of these questions is perhaps slightly disingenuous. Social utility and the public good were important to the members of the Association but in their hierarchy of values it was not the highest. On that scale questions 1 and 3 might have changed places. It was the bush they championed over everything else. It was not that they believed that other claims about the use of public land could not be legitimately made but simply that they believed that those other competing interests were well-represented in such debates already, perhaps over-represented. The bushland on the other hand had historically lacked advocates to stand up and argue for its preservation as bushland, disregarding its potential as available space for playing fields, car-parking and so on. This situation was not helped by the woolly thinking and indetermination on the part of the public and government. What is a park? What is a reserve? What are they for? Should a distinction be made between active and passive enjoyment of such places? What is meant by the terms natural and primitive?

In a newspaper article of Nov 1966 Joan Bradley said that it would be as wrong to suggest the development of Hyde Park in the city as natural bush as it would be to proceed with this sort of plan for Ashton Park

Sensing perhaps a shift in the breeze of public opinion and a corresponding reaction from the new Minister for Lands Tom Lewis, Sir Edward Hallstrom retired in 1967 at the age of 79, just before a government report found that the financial and material position of the zoo had declined substantially. He was succeeded by Ronald Strahan, a professional zoologist who ran the zoo properly for the next seven years. In 1967 too the Ashton Park Trust shelved the Master Plan and also, importantly, in that year the National Parks Bill was enacted in federal parliament.

Another assault on the bushland of Ashton Park had come in the winter of 1965, a drought year. On July 8th Michael Kartzoff of the NSW Forestry Commission carried out the burn which he had advised the Ashton Park Trust would be necessary in order to promote new growth and to reduce the fire hazard, two aims on the face of it not easily reconcilable with each other. Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned … went the by-line in the local newspaper and then less poetically …But when it comes to seven women – hell is certainly not in the race. According to The Mosman Daily Eileen and Joan Bradley, June Gram, Audrey Lenning and three other women hooted and chirped over the crackle of the flames, mounting an unfair vocal assault on the hapless and slightly bewildered Mr Kartzoff. It must have looked as if King Lear had stumbled into a production of Macbeth

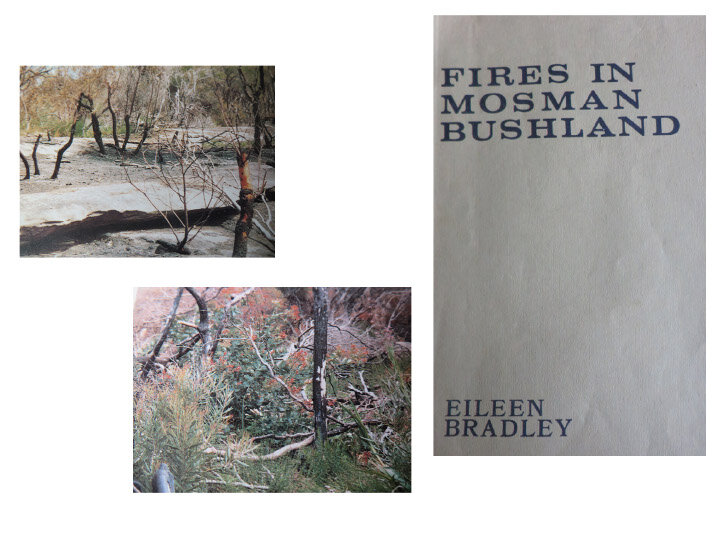

The role of fire in the modern Australian environment was of growing interest to the association and in later years they helped to organise several seminars which gathered stakeholders together to attempt to work out policy and strategies around this ‘burning issue’. At one of these Joan gave a paper titled ‘Aborigines and Fire’. Eileen or Joan Bradley was asked by the National Parks Association to write a book on the subject of Fire. Eileen gathered their own observations and research together and published a paper titled Fires in Mosman Bushland.

Both of these were worthy attempts to come to grips with a complex subject about which little was understood. The subject was then and remains very controversial. I would refer you to the new one-size fits all 10/50 ruling proposed by the RFS recently, a giant leap backwards, and one which is currently being energetically challenged by conservationists and local councils, including Mosman Municipal Council.

In the winter of 1968 the conservationist Allen Strom gave a talk to the members of the association which clearly influenced their thinking and which they published afterwards. Before the National Parks Bill of 1967, designating parks or reserves as primitive or natural areas seems to have been a means of avoiding having to do anything about them, so that in the case of Ashton Park until 1964 the most primitive thing about this so-called primitive area was the management vacuum in which it existed. Allen Strom had taken over in The Wildlife Preservation Society from the pioneering conservationist David Stead who had been one of the first people to recognise in the early twentieth century that Nature, natural areas, [have] to be protected in statutory and legislative frameworks. Before that can happen there has to be some kind of public debate and philosophical consensus. Strom pointed to two national parks close to Sydney, the Royal and Kuringai Chase, where confusion about the quality naturalness had led to huge pressures on the environment from active recreational uses such as boating and horse-riding. He also pointed to Kosciuszko National Park in which snow sports and hydro-engineering had made fantastic inroads since the war, as snow leases for graziers in Spring had done for decades. In other words, these parks existed in a society confused about their proper functions and value, although in the minds of most people their greatest value probably was still that they represented available space. In terms of small natural or bushland reserves Strom pointed out that the size may be such as to make their demise only a matter of time, especially if they exist as did several in Mosman in isolation from other natural reserves. And of course, urban reserves are always particularly vulnerable to perceived community needs for active recreation.

Above: Not much has changed since 1966!

Batting these away over the last 50 years has been a large part of association members’ efforts and our lovely suburb would be much less lovely today had this not been so.

In 1967 aged 51, her credibility thoroughly well–established because of The Critical Evaluation and her B Sc, and perhaps despite her gender, Joan Bradley was appointed to The Ashton Park Trust, at which point she resigned from holding office in the Association.

A newspaper photograph of the new board shows Joan slim, fair-haired and elegant in a pale knitted dress, grinning broadly and positively shining out of the row of dark suits. Her satisfaction no doubt arose in part from the knowledge that with her custodianship thus officially recognized she would from then on be well-placed to look after the bushland at the political level; it may also have derived from a consciousness of the leverage her new status would give her in all the differences of opinion she and Eileen would continue to have with Charles Martin, the Ashton Park factotum, over management issues on the ground. Martin was evidently a hard- working man who functioned as a sort of hybrid gardener, ice-cream vendor, path maker builder.

At around this time too, The Ashton Park Trust published a booklet for the use of visitors which was written by Joan Bradley and illustrated by the botanical artist Betty Maloney. Joan described the Angophora costata, a tree with such graceful well spaced boughs and light leaf cover that it might have been designed specifically for the contemporary water-view hungry real estate market.

A fabulous tree which indeed seems in places almost to be an extension of the sandstone, the roots and branches the same colour as the unweathered rock. Its bumpy yet sinuous form can also seem startlingly like a human torso and limbs. To the poet and nature lover James McAuley, who in the 50s and 60s worked at ASOPA at Middle Head, it seemed that the Angophora … preaches on the hillsides with the gestures of Moses.

In 1965 the association widened its brief in response to the Defence Department’s plans to bulldoze bushland along the ridge line at Middle Head for army housing. The Association was then renamed The Mosman Parklands and Ashton Park Association the aims of which were to:

resist the destruction and alienation of Mosman’s bushland and parks;

restore and regenerate bushland areas in Mosman; and

encourage good principles of town planning.

At around this time too, the association started campaigning to save the damp ridge top heathland at Rawson Park from development. The NSW Dept of Health and the Education Dept were at different times eyeing it off as available space for a hospital or school. In 1966 the Bradleys began investigating the native flora at Rawson Park, making several surveys over the years which are still considered authoritative.

The Association had all this time been busy not only at the political level however; a quiet revolution had been taking place literally at the grassroots, the effects of which would eventually be felt far and wide.

By the time the Association was formed in 1964 the Bradley sisters had been observing for years the encroachment of weeds in the bushland near their small cottage in Iluka Rd, and at one of the first meetings of the Association Joan showed photographic evidence of the extent of the problem. It was proposed that voluntary labour be recruited to get in and start hacking away at the weeds but a dissenting voice, no doubt one of the Bradleys’, suggested that the job was too big for such an approach and that areas of healthy bush might be damaged in the process. Instead it was decided that the Association should inform the Trust of the extent of the problem and urge that a program of progressive eradication be initiated, followed by replanting with native plants.

By August the Trust had begun a weed eradication program. In September 1964 Joan gave the Ashton Park Trust a list of plants suitable for replanting but by May 1965 the matter was still under consideration, while the clearing of weeds by mattock, hoe and brush hook proceeded. The weeds of course, finding the disturbed ground and increased light levels to be ideal and not having to consult and seek advice, grew back stronger than ever all through that Summer.

On behalf of the new Ashton Park Board Joan Bradley approached The Wildlife Preservation Society and asked them to make a general census of plants in Ashton Park. The Association also formed relationships with botanist and teacher Thistle Harris, widow of conservationist David Stead of The Parks and Playground Movement of NSW and with The Society For Growing Australian Plants. All this was in an effort to find the best means of replanting the cleared areas.

In October 1965 the Bradleys and other Association members began collecting specimens and propagating seed. It seemed obvious that clearing followed by replanting of the cleared ground must be the answer. In other words, it appeared that the solution to the problem of weed invasion was twofold. Council engineers and labourers, knew how to tackle the first stage but clearly replanting was a different sort of operation altogether and no-one really knew how to go about it, what sort of stock to plant, where to get it and how to maintain it.

Other members of the Association would later recall that Joan was always going on about the weeds. Her knowledge of plants seemed to them prodigious and it was. Joan had ‘done’ basic biology at university, but she also depended on the staff of the National Herbarium at the Botanic Gardens for anything she had not confidently ID’d herself. She would make the journey across the Harbour Bridge to the finger of land on which the herbarium is situated. Former staffers remembered her parking the Morris Minor and tying the dog to the bumper bar with a bowl of water while she went inside with her carefully dried and displayed specimens, a skill the sisters had learned from their mother. She always had done her own research and was prepared to argue the point until convinced otherwise. Sometimes she was right and sometimes she was wrong.

The Bradleys’ associates at this early stage did not realize how closely Eileen and Joan had been looking at Ashton Park for the previous fifteen years, while walking the dogs and doing their bird surveys. They were all pleased that at last the Trust was doing something about the weeds, but it was realised early on that whatever they were doing was not really working, could indeed even be making the problem worse. It became obvious to the Bradley sisters that opening up disturbed patches of ground to the light encouraged rapid regrowth of seed–banked, bird dropping dispersed or windblown free-seeding exotics and that these secondary colonizers were sometimes a worse problem than the weeds they had replaced. Leaving the ground bare after clearing also exposed it to the risk of soil erosion under adverse conditions. Eileen and Joan had long before realised too that in the absence of native vegetation fauna such as the ground-dwelling blue wrens can make nests in weedy, woody shrubs like lantana.

Eileen and Joan watched from the sidelines as the labourers belted, uprooted and burned the weeds, and they helped by going in afterwards and raking up the debris. Revisiting the cleared sites’ they saw the weeds growing back lustily. The Association urged the

Trust to undertake a replanting program as soon as possible so that the advantage gained by clearing could be held. Back on the ground while waiting for the slashing and burning operations to finish so that they could go in and tidy up, Eileen and Joan began to pull up stray weeds where they stood, at the edge of the theatre of operations, near relatively good bush. When they returned to these sites later, they realized that in these relatively good areas along the margins of the cleared areas, that is at the interface of cleared areas and bush, the native plants were growing back by themselves. This is how Joan later explained it in a letter to their friend the native garden designer Jean Walker …

We always pulled up weeds in passing. We started by just drifting into it ….. In 1964 the Council hacked away at Ashton Park. Of course, it grew back into lantana practically overnight. We didn’t dream of following it up. The Council belted, burned and uprooted weeds and we helped by clearing it up. As we began to pull stray weeds in good bush we could see that the bush began to help itself and we found tremendous delight in attacking just one weed and covering up just a little hole …

It was in this way the Bradleys realized that native plants once freed from competition form a stronger front and so are able to recolonise the edges of the patches of cleared earth adjacent. In other words, weed eradication was most effective if it began not where the weeds were worst but where the natives were strongest. This was a radical idea, counter-intuitive even, but Eileen and Joan thought they were onto something and began systematically to apply this principle in their weeding practice in Ashton Park, making careful notes as they went. They wrote up their conclusions in a paper called Weeds and Their Control which the Association published in 1967

Weeds and Their Control was an attempt to come to grips with the weed problem in one particular area, Ashton Park. It was based on the casual observations the Bradleys had made during the period 1950 – 1962, the records they had kept in their field notebooks since 1962 and the weed surveys they made with the Association in 1964, 1965 and 1967. With this info they drew a weed map.

The Bradleys and the other members of the Association felt that their conclusions should be of interest to anyone concerned with the maintenance of urban bushland reserves.

The failure of various attempts at replanting is then discussed (rabbits were a real curse of course) and some general recommendations for weed removal made, broadly stated as work from good areas to bad. Replanting was regarded as a last resort for those areas where natural regeneration could never succeed because of the lack of enough good, clean bush to recolonise the cleared areas and because of on-going human impacts on those areas. The importance of follow-up weeding sessions was emphasized. By 1968 Eileen and Joan had proved to their own satisfaction that their methods worked and they then made an addendum to Weeds and Their Control … with a map showing the stabilization of half a hectare of bush, including part of a site, cleared by crude methods in 1965, which by 1967 had reverted to lantana well above our heads.

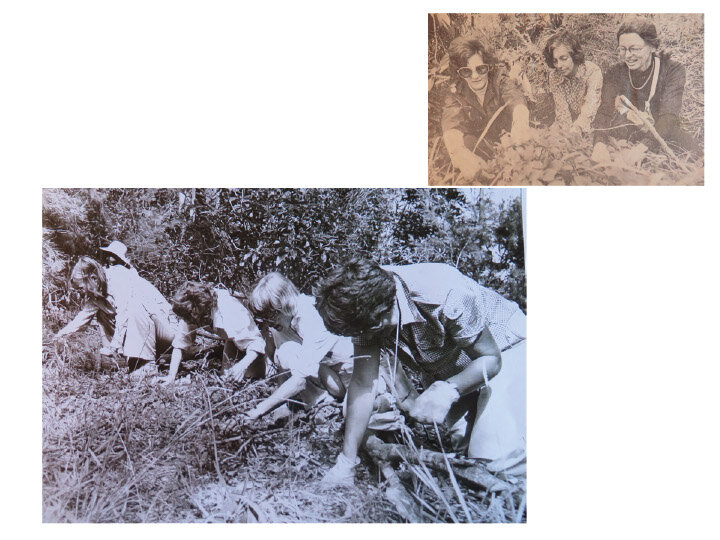

With the publication of Weeds and Their Control the Bradleys demonstrated the value of their ideas and various members of the Association joined them in doing selective hand-weeding in some Mosman Council owned reserves and in Ashton Park. With the permission of the Council they weeded in rotation the reserves at Morella Rd (Chowder Head), Parriwi Park (near the Spit) and Rawson Park (on the top of the ridge at Middle Head).

Barry O’Keefe would entertain by singing funeral dirges in Latin, quite a different style to that of his more famous brother Johnny. It was during one of these happy working parties that the term Bush Regeneration was coined, as Association member Audrey Lenning later recalled …

During the break discussion came round to the sign ‘Weeders at Work’ – weeding seemed rather a negative activity – what we were doing had a positive aspect. I don’t remember what words were used exactly but we talked of encouraging the bush. Ideas and words were tossed around until finally (I don’t remember whose brilliant idea it was) someone said ‘regenerator’ which was unanimously accepted. The board was altered and amusingly for many months we worked behind a notice which read ‘Bush Regerators at Work’ It took a seven year old’s question “What does regerator mean?’ to alert us to the missing ‘en’.

Association members e.g. Barry O’Keefe also served on Mosman Council but the numbers there rarely favoured the conservationists’ causes. As in the world at large there was at Council a clash of two fundamentally different kinds of people: those like the Bradleys and their associates who treasured the natural world, understood their dependence on it and cooperated in protecting it, and those who tried to exploit or master Nature as part of a generally competitive dog-eat-dog approach to humanity and Nature alike, especially if there was a buck in it for someone.

I will begin this part of my talk with a couple of quotes, the first from Francis Bacon:

“the father of the modern scientific method: “All depends on keeping the eye steadily fixed on the facts of nature, and so receiving their images as they are. For God forbid that we should give out a dream of our own imagination for a pattern of the world.”

And the second from Joan Bradley:

“Bush regeneration fails if you treat the task like gardening. Gardeners expect to keep cultivating, and don’t expect roses and pansies to spring up of their own accord. You use the naturalist’s approach, and help the bush to help itself, you can expect the native plants to do just this. “

In the 1970 annual report of The Mosman Parks and Bushland Association it was noted that ‘Misses E and J Bradley have perfected a method of selective weed removal and this has been successfully used for regenerating bushland in the park and on Chowder Head.’

In June 1971 The Association published Bush Regeneration by Joan Bradley.

Bush Regeneration represented a development of the ideas first put forward in Weeds and Their Control. The positive response to their first publication had encouraged the association members in the belief that these ideas might be more widely useful. Since 1967 they had applied these ideas, as we have seen, at various sites in Mosman and during this time a change of focus had occurred. The encouragement of natives, not the eradication of weeds, had become the primary goal. It was all about loving the natives, not hating the weeds!

It was a subtle but very significant shift in emphasis which enabled the Bradleys to better come to grips with the issues of timing and direction. If weed removal is the primary goal of an operation then one goes as far and as fast as one can, but if thinking of the regenerating natives then one goes only as far, as fast as the bush can follow, or as far and fast as there are resources for follow-up weeding. Although fairly simple in principle this is more problematic in practice: determining out in the field just how much regrowth of natives will occur in what period of time is a matter of familiarity with a specific site, its flora, climate and ecology in general.

The three principles of Bush Regeneration were expressed in this 1971 volume [for the first time] as:

work from good areas to bad;

keep the soil deeply mulched (later expressed as ‘Disturb the soil as little as possible’); and

allow Regeneration to Dictate the Rate of clearing.

It seems that Bush Regeneration was an idea for which the time had come. The post-war population and housing boom had, in the greater Sydney area, greatly exacerbated the conditions which favour weed growth, chiefly disturbed soil and increased run-off from hard areas. At the margins of suburban Sydney more and more land had been cleared as the built environment pushed out into the surrounding bushland; it was getting harder to ignore the damage caused not just by the primary clearing but by the largely accidental translocation of exotic plants and pests across the boundaries of gardens and parks into the bushland and by the increased and nutrient enriched run-off from the new hard surfaced areas.

Some years ago I spoke to Betty James of The Battlers for Kelly’s Bush. Kelly’s Bush was a piece of foreshore bushland reserve on the lower Parramatta River at Hunters Hill (or upper reaches of Sydney Harbour) which the developer AV Jennings was determined to acquire. Betty recalled when we met, that at the first meeting of ‘ The Battlers’ in 1970 she got up very nervously to speak and saw two faces positively radiating encouragement from the front row, Joan Bradley’s and June Gram’s. The three women talked after the meeting and The Battlers bought two copies of Bush Regeneration with which to fight the good fight at the biological level, the grassroots. It was important to restore degraded sites like this because the fact that they were unkempt and weed-infested played into the hands of the developers, who could point to their condition as evidence that the sites were unlovely, unloved and useless. A classic case of blaming the victim. They also learned a lot, she said, from the Mosman Parks & Bushland Association about lobbying.

In the 1970s also conservationists in Lane Cove adopted the techniques of bush regeneration at Gore Creek, another arm of the waterway, with relatively rich washed-down shale soils which had been used for market gardening and then as a rubbish dump. So clearly degraded, weed-infested and useless was this site deemed to be that the members of the neighbouring golf club applied to Council to acquire the land in order to extend their nine hole golf course.

This appears to have galvanized some locals to demand, successfully, that the application be rejected and that the site be retained as a public bushland reserve. In this they were successful.

The publication of Bush Regeneration had come just in time for these sites, as it did for Mowbray Park in Willoughby, where in 1971 the Council attempted to put an oval and a road in and dump material there. Evelyn Hickey, a local conservationist, introduced herself to the Bradleys who impressed her deeply with their knowledge of the vegetation of Mowbray Park. She took home a copy of Bush Regeneration and with her associates began successfully to apply the principles there.

From here bush regeneration travelled to Beecroft where the National Trust has managed the L Blackwood reserve, a remnant of blue gum high forest, since inheriting it in 1961. Evelyn Hickey took Bush Regeneration to the National Trust who decided to use bush regeneration at Beecroft. Because of the support of the National Trust at this site, bush regeneration was well and truly out in the world. One volunteer regenerator here was Robin Buchanan, a biologist who went on to develop the TAFE course in what is now I think still called Natural Area Restoration. I was lucky enough to have Robin as a teacher when I did this course in 2006, a fine ecologist and teacher

Most councils in the Sydney Basin now have budgets for bush care and dedicated staff members to support volunteer groups and also $$$ to spend on contractors. Mosman Municipal Council for instance has for many years supported such activities. The original

members of the Association would be proud that their efforts have helped to restore and maintain the richness & diversity in our local bushland and much further afield.

by ANN COOK