Community responds at public meeting to discuss proposed new buildings on Middle Head

ABOVE L TO R: Jill L’Estrange, Dr David Robertson, Kate Eccles

Mosman Parks and Bushland Association (MPBA), in conjunction with The Headland Preservation Group (HPG), held a public meeting on 21 February 2024, to inform the public about the proposal by School Infrastructure NSW (SINSW) to establish an Environment Education Centre (EEC) at Middle Head / Gubbuh Gubbuh.

The meeting room was at capacity, with 90 members of the public attending. Public concern regarding the direction of the proposed development was evident at the meeting. Kate Eccles, President of Mosman Parks and Bushland Association; Dr David Robertson, Director of Cumberland Ecology; and Jill L'Estrange, President of HPG, addressed the meeting outlining the deleterious ramifications of amending the Plan of Management to allow new buildings in the precinct. Read their addresses below.

“An Environment Education Centre is a wonderful idea, but a NEW building should NOT be built in the National Park at Middle Head. The National Park is a loved and beautiful part of our country’s story. There is an alternative for an Environment Education Centre in a different part of Middle Head where there are suitable EXISTING buildings. The environmental and heritage values of the National Park need not be lost.”

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Write make a submission to the NSW department of education. Because your feedback will will not be made public please share your feedback with HPG and MPBA.

THOSE PRESENT AT THE MEETING UNANIMOUSLY RESOLVED TO APPROVE THE FOLLOWING MOTION:

The Sydney Harbour National Park at Middle Head is a precinct of exceptional environmental, First Nations, colonial and military heritage values.

It is also a precinct of national historic significance.

No new buildings should be built in the Sydney Harbour National Park at Middle Head.

Amendment of the Sydney Harbour National Park Plan of Management to allow new building for the establishment of an Environment Education Centre at Middle Head is not supported.

An Environment Education Centre located at the 10 Terminal precinct at Middle Head on land managed by the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust is supported.

Transcript: Jill L’Estrange, HPG President:

INTRODUCTION

A fact unknown to many is that Middle Head is managed by both State and Federal Governments: National Parks and Wildlife NSW (NPWS) manages much of the foreshore and the historic precinct known as Middle Head Fort. The Sydney Harbour Federation Trust (Harbour Trust), a statutory Commonwealth Agency, manages the ex-defence lands on the Middle Head plateau adjacent to Middle Head Fort.

PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT AT MIDDLE HEAD FORT

School Infrastructure NSW (SINSW) plans to construct an Environment Education Centre at Middle Head Fort in the Sydney Harbour National Park. The project aims to support the cultural values of the existing site and increase its use by providing facilities for up to 120 students per day from Kindergarten to Year 12.

It is intended to use the heritage Soldiers Institute as 2 classrooms. The building will require minor internal refurbishment to facilitate this.

The proposal, however is also to build a Covered Outdoor Learning Area (COLA), staff facilities, student amenities and storage, accessible driveway and mobility parking spaces.

SINSW states that it is working closely with NPWS to deliver the facilities.

Currently, the statutory Sydney Harbour National Park Plan of Management (PoM) prohibits new buildings at Middle Head. This Plan would need to be amended to allow the COLA and supporting structures to be built.

We are meeting tonight because SINSW has failed to adequately inform the community of the details of its proposal.

BACKGROUND TO DATE

In October 2022, SINSW announced the project. Of course, this was under the radar for most people – only those identified with a vested interest were contacted.

The announcement included an artist impressions of the COLA and Plan.

The style and bulk of the new buildings caused great concern, and it was clear that the project was well under way.

At that stage SINSW (SCHOOL INFRASTRUCTURE) had:

Established a Project Reference Group (PRG) including representatives from the Department of Education, NPWS, expert heritage consultants, planners and design professionals.

Engaged a heritage consultant to provide advice on the existing Soldiers Institute

Engaged NPWS to workshop the design proposal, general usage arrangements and planning considerations.

Appointed an architect to develop the design consultation with the Project Reference Group (PRG)

So this project was well on the way! It is clear that SINSW has already invested substantial funds in the project to date.

Also

At the same time, on 21 October 2022, NPWS announced its draft amendment to the SHNP PoM to allow the construction of new buildings to enable the development of the proposed EEC to be considered at Middle Head.

As it currently stands, no new buildings are allowed on SHNP land at Middle Head.

In January 2023, HPG lodged a submission with NPWS detailing why it opposed the amendment of the PoM, allowing the construction of new buildings and associated infrastructure for an EEC at Middle Head Fort.

NOW, I wish to make it clear that both HPG and MPBA support an Environment Education Centre at Middle Head.

We DO NOT, however, support NEW BUILDINGS in the heritage precinct of Middle Head Fort, especially when there are existing unused buildings 200 metres away suitable for such a use.

HPG'S HISTORICAL INVOLVEMENT IN THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE EEC

In 2016, HPG Vice-President Julie Goodsir wrote a proposal for an EEC at Middle Head, being a suitable adaptive reuse for 10 Terminal.

In early 2017, Julie submitted the proposal to the Department of Education and, together with HPG, presented it to the then Minister for Education, Rob Stokes, who endorsed the proposal.

We understand that the Dept of Education had conversations with the Harbour Trust regarding a suitable location on Trust land. At that stage, 10 Terminal, HPG's preferred option, was in a derelict state, and the project did not proceed.

In 2019, two pilot days were held to review the project's feasibility.

In October 2022, we learned that the NSW Dept of Education has entered into an arrangement with NPWS for the EEC to be located at Middle Head Fort.

WHY DO HPG AND MPBA OPPOSE NEW BUILDINGS AT MIDDLE HEAD FORT?

A new building of the proposed scale will detract from this national site's important environmental, First Nations, and heritage values.

The visual presence of the COLA will dwarf the adjacent heritage Soldiers Institute, be immediately visible upon entry to the heritage-listed precinct and visually impact the natural environment.

The proposed development is a gross waste of NSW taxpayers' money when suitable alternative accommodation is available in the nearby 10 Terminal.

Amendment of the Sydney Harbour National Park Plan of Management to allow NEW BUILDINGS at Middle Head risks creating a precedent for the construction of more new buildings in the precinct in the future.

With the potential for increased tourism as a result of the 80km Bondi to Manly Walk and the activation of the 10 Terminal site, visitors will likely be excluded from walking through and enjoying a public area of historic interest.

The project requires the destruction of significant bushland near the public pathway to the Middle Head Outer Fort. A core objective of the NPWS under the National Parks Act is to preserve the biodiversity in its parks.

Also

Any decision to allow NEW BUILDINGS at Middle Head Fort goes against the:

SHNP Statutory Plan of Management.

Sydney Harbour National Park Middle Head Historic Buildings Conservation Management Plan.

State Heritage Listing.

These documents outline the national significance of the site. Why has the detailed heritage analysis in these documents been ignored?

Before we go any further, I would like to give a quick overview of the heritage values of this site.

THE SIGNIFICANT MILITARY AND COLONIAL HISTORY OF MIDDLE HEAD FORT

Middle Head Fort, comprising the fortifications and the group of remaining buildings, illustrates many important themes in Australian heritage.

Nowhere else in Australia has there been such a continuous occupation of a military site from 1801 to the Vietnam War. Historical experts say it is unmatched elsewhere in Australia. The fortifications from different periods show the development of coastal fortifications and defence technology over two centuries.

1801 Fort

The fortifications at Middle Head commenced with the construction of the 1801 Fort by the convicts, hewn by hand from a sandstone outcrop.

Middle Head, even back then, was identified as commanding the entrance to Sydney Harbour and would provide an 'outer defence' of the colony. Britain was concerned about the French interest in the southern oceans.

Future fortifications were also built in response to perceived threats by Britain from other imperial powers.

Early contact with Aboriginal Inhabitants - Bungarees' Farm 1815

In this location, there is well-documented evidence that the first contact between colonial forces and the original Aboriginal inhabitants occurred as early as 1788. On 29 January 1788, Lieutenants Hunter and Bradley were said to have interacted with and danced with the Aboriginal people on the beach (Cobblers Beach).

Later in 1815, Middle Head was the site of Macquarie's experiment to 'civilise the natives'. Macquarie granted land to King Bungaree (Macquarie's favourite). This was an attempt to teach the Aboriginals European farming methods. The project was eventually abandoned in 1822.

1853 – 1870 Crimean War Activity

Early site development occurred during the Crimean War, 1853-1856, primarily involving Britain and Russia. This was Britain's response to Russia's presence in the northwest Pacific, which was considered a threat.

Construction of a battery commenced at Outer Middle Head in 1854, but it was halted 6 months later by Governor Denison, who felt that the protection of Sydney Cove was more useful and that the Middle Head development was complicated by the difficulty in "manning such extensive and distant works".

1871-1882 Sydney Stands Alone

In 1870, when the last British troops left the Colony, Australia was faced with the responsibility for its own defence.

Due to the need for NSW to develop its own self-defence, the main period of fortification of the precinct began in 1871. This was the construction of the outer line of defence: Outer Middle Head and Inner Middle Head Forts.

With the construction of these Forts came the first permanent accommodation. In 1876, weatherboard barracks and a Guardhouse were built – firstly for the Engineers Corps building the fortifications and then later for the artillerymen.

The historic buildings within the barracks area are intrinsically related to the general historical significance of the Middle Head fortification works. The barracks appear to have housed the military personnel charged with protecting the gun emplacements in times of war, whose purpose was to train with guns in times of peace.

Not only were the barracks built, accompanied by outbuildings such as kitchens, pantries, latrines and stores, but the most impressive building on the site, the Victorian Regency Officers Quarters, were also built. The Officers' Quarters built in 1880 still exist today.

By 1890, the moat and defensive wall were built, enclosing the Barracks and fortification sites to provide further protection.

1883-1911 From harbour defence to coastal defence

The most important aspect of this phase was the establishment of the School of Artillery in 1885.

The School of Artillery was perhaps prompted by the fall of Khartoum in the Sudan, in which NSW troops participated in their first overseas involvement. Between 1886 and 1911, men of all ranks completed gunnery courses at Middle Head. These courses eventually led to the establishment of the modern School of Artillery at North Head.

The three buildings constructed during this period are the Sergeant's Majors Quarters (MH30), Guardhouse (MH32) and The Soldiers Institute (MH31). These buildings also remain intact today.

1912-1938 World War I to the outbreak of WWII

"Surprisingly, Middle Head appeared relatively quiet during this period, especially during WWI when overseas action was so intense. Australia's isolation from the centre of action ensured that while defence stations were kept on the alert, their activities remained basically the same as they were before.

The Battery's primary function seemed to have been administration, training, mobilisation and supply". (P17, Sydney Harbour National Park, Middle Head Historic Buildings, Conservation Management Plan, by Paul Davies Pty Ltd 2003 [CMP]).

1939- 1945 The war comes to Sydney

In 1939, Australia was again on a war footing. Middle Head once again sprang to life, designated a close Defence Observation Post.

Middle Head became a training camp, and the militia were housed in huts. By the early 1940s, it was a substantial encampment.

Buildings on the site underwent changes in response to the wartime situation. For the first time women had a presence on the site as signallers and observers. The Officers' Quarters became the Red Cross Hospital.

The wireless station's communications function (previously the Guardhouse) was intensified during WWII when it was used for more general intelligence communications monitoring.

1946 After the end of WWII

"While technical operations wound down on the site after the war ended in 1945, the residential buildings underwent a flurry of activity. The returning troops needed accommodation, and the army records are crammed with specifications for repairs and conversions of existing buildings, mainly barracks huts, to married quarters" ( P19 CMP).

Before the defence handover of the site to NPWS in 1980, the major barracks building had been demolished – the site is noted as having a high degree of archaeological potential.

Vietnam – 1962-1973

The first Australian Army Training Team contingent for deployment to Vietnam in 1962 was given Code of Conduct training at the Army Intelligence Centre on Middle Head.

This training included being locked in special cages in the tunnels beneath the Middle Head Outer Battery Gun emplacements. The soldiers were subject to intensive interrogation, being part of the training for resistance to interrogation should they be captured by the enemy. This training was colloquially called the 'School of Torture'.

ABOVE: The simulated tiger cages used in training at Middle Head.

Conclusion

As you can see, the site is an important place for its role in military training, its demonstration of early military accommodation, and its place associated with important military events, especially WWII. It has strong associations with a large group of people who trained on the site, is an icon for those who have associations with the defence force and is related to the role of women in the forces.

In addition to the above First Nations and military significance of the site Any decision By NPWS to allow new buildings at Middle Head Fort goes against the following:

SHNP Statutory Plan of Management.

Sydney Harbour National Park Middle Head Historic Buildings Conservation Management Plan.

State Heritage Listing.

STATUTORY PLAN OF MANAGEMENT

This Plan recognises the importance of conservation and interpretation of the precinct's highly significant Aboriginal and historical values.

The Plan states:

"Middle Head precinct holds important cultural significance for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people alike".

Not only is "Bungarees Farm,… known to be located in this area", the precinct is part of the "exceptional collection of Aboriginal archaeological heritage not found elsewhere in metropolitan Sydney". It is noted that Aboriginal rock engravings occur in the precinct.

"The precinct contains an exceptionally significant, extensive collection of fortifications and associated structures".

The precinct is a key destination for visitors to the secluded beaches, walking tracks, historic sites and nearby facilities on Harbour Trust land.

SYDNEY HARBOUR NATIONAL PARK MIDDLE HEAD HISTORIC BUILDINGS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN (CMP)

This Plan was commissioned by SHNP. It examines in detail the military structures that supported the nationally significant function of the Middle Head fortifications.

Although the barracks area contains only remnant structures – there remain enough surviving buildings to understand the site.

"The site layout demonstrates details about the strategy of the fortifications, their protection and surveillance and the influence of British military advisers on the colonial military forces.

… The historic building group expresses the distinct military hierarchy between officers and other ranks.

… Buildings range from Victorian Regency buildings to small vernacular structures with the Soldiers Institute (the site of the EEC) being at the upper level of building quality. They shared however common building materials with a predominance of weatherboard cladding."

The buildings and site features demonstrate the influence of important figures of the Victorian period such as Colonial Architect James Barnett, Colonel de Wolski, and the British military advisors who shaped Sydney's early defence patterns.

The site also has a high degree of archaeological potential.

THE PLAN ASSESSES THE HISTORIC BUILDINGS OF THE BARRACKS AREA AS "A PLACE OF HIGH SIGNIFICANCE – A SITE OF IMPORTANT HISTORIC MILITARY ESTABLISHMENT".

The Plan states further that "NEW BUILDINGS WITHIN THE CONFINES OF THE MOAT PERIMETER WOULD BE AN INAPPROPRIATE RESPONSE TO THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SITE AS A WHOLE. IN PARTICULAR THE INTERRLEATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THE BUILDINGS SHOULD NOT BE OBSTRUCTED BY NEW BUILDINGS".

NSW STATE HERITAGE LISTING

Refers to the historic buildings within the barracks area as being intrinsically related to the general historical significance of the Middle Head fortification works.

Criterion(f) states that "The Middle Head Barracks and fortifications are a rare example of a relatively intact military establishment designed from the earliest period of colonial responsibility for the defence of Sydney Harbour".

The listing also notes that the headland is part of a "unique aesthetically significant landscape.. which form a strong element of the image of Sydney".

"The area had regional importance as part of the city's protection through its growth as a port and settlement over the past two hundred years.

Why are these values being ignored by NPWS and SINSW?

HPG and MPBA are of the opinion that these values cannot be ignored at any price!

To denigrate our heritage in such a way is to shun the history of our nation.

Middle Head is of national significance because of its irreplaceable Aboriginal and Military heritage and its significant natural environmental values. It is located in the heart of one of Australia's major cities. It is an integral part of Sydney Harbour, which is renowned not only nationally but also internationally.

Such a prominent national asset must be protected.

THE CURRENT POSITION

SINSW has advised that planning to deliver the EEC is underway.

In February 2023, the Heritage Council of NSW Approvals Committee met to review the EEC proposal – informing the design and location.

In September 2023, a Bushfire Risk Assessment Report was prepared. It identifies a bushfire risk associated with the construction of the COLA. It requires an asset protection zone to be maintained around the COLA.

This of course will require the removal of a substantial area of native vegetation. To destroy bushland and impact the biodiversity of SHNP unnecessarily is contrary to the core purpose of NPWS, which is to conserve and enhance the natural and cultural values of the entire headland.

In August 2023, SINSW consulted with the Harbour Trust to investigate options for locating the EEC in building 6 and/or 7 in the existing 10 Terminal. The Harbour Trust has indicated that it is interested in exploring this option.

SINSW however states that "This option will only be considered once the review of options for the location at the Soldiers Institute has been completed.

In other words, SINSW will only consider the alternative location of 10 Terminal if the proposed amendment of the SHNP PoM is disallowed.

The decision to approve the amendment will be made by Minister Penny Sharpe based on the assessment of heritage and environmental reports to be provided by SINSW. These reports are assessed by NPWS and Heritage NSW and their recommendations are made to the Minister.

This process is concerning. It appears that NPWS is working closely with SINSW to facilitate this development, and yet they will take part in the assessment of the heritage and environmental reports.

Isn't it ironic that the proposal to build an EEC to teach children the important values of the environment (natural and built) will destroy natural bushland and adversely impact the built heritage values of the area.

It makes a mockery of such a development proposal!

We must remember that there is an alternative solution! 10 Terminal.

– end transcript Jill L’Estrange –

Transcript: Dr David Robertson, Director of Cumberland Ecology, Chair of the Mosman Environmental Foundation

Thank you. I hope to add to some of the information presented in the really good talks before me and bring out a few points from my area because I'm a consultant ecologist. I study plants and animals.

I've had an opportunity to look at the site. I've visited it. I've also had an opportunity to use some of the mapping tools that we've got available to us as ecologists and looked at some of the flora and fauna values of the site.

So, I've got a very brief presentation tonight to give you my views about what has been done, what's been presented to you to date, and what can be done to take further steps to look into this.

You can see (ABOVE) that the COLA is highlighted here in orange, and the surrounding area is cross-hatched in green and yellow stripes. And that's for the asset protection zone. In an asset protection zone almost all of the vegetation has to be cleared. They can leave a shrub or two, but it's entirely cleared for all intents and purposes.

That would be the impact of that development. But I want to look more closely at the implications of that. In 2016, in New South Wales, new legislation was brought in called the Biodiversity Conservation Act, which at its core has a theme. It's a hierarchy of assessments you must go through when developing a proposal to build in a natural or semi-natural environment. And it basically says that you should first consider avoiding the impacts of the development to begin with. You need to see if you can design a development that doesn't need to have an environmental impact. Can you do that? That's the first thing built into the legislation. So that's the Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Then, it says you must consider the opportunities to mitigate that impact. Is there anything else you can do to soften any edge effects or impacts on native flora and fauna? It requires that you look at the vegetation types, whether or not the vegetation is endangered or unusual, and whether or not there are threatened plant and animal species that live within it that could be impacted.

And finally, when all else is said and done, and you elect to have a development in that location, and you can't avoid it, or you don't think it's worthwhile avoiding it, then you can create what's called offsets to offset the impact of it. The notions of going through that process are important because if you're developing a site that's zoned for residential development or for some other type of development, that may well be a good idea to press for a certain level of development.

But first and foremost, we need to remember that this is right in the heart of the city and in the Harbour National Park. So it's a National Park that was gazetted in 1975. It's there expressly for the purposes of conservation. The avoid, mitigate and offset hierarchy is important to consider in the context of a National Park.

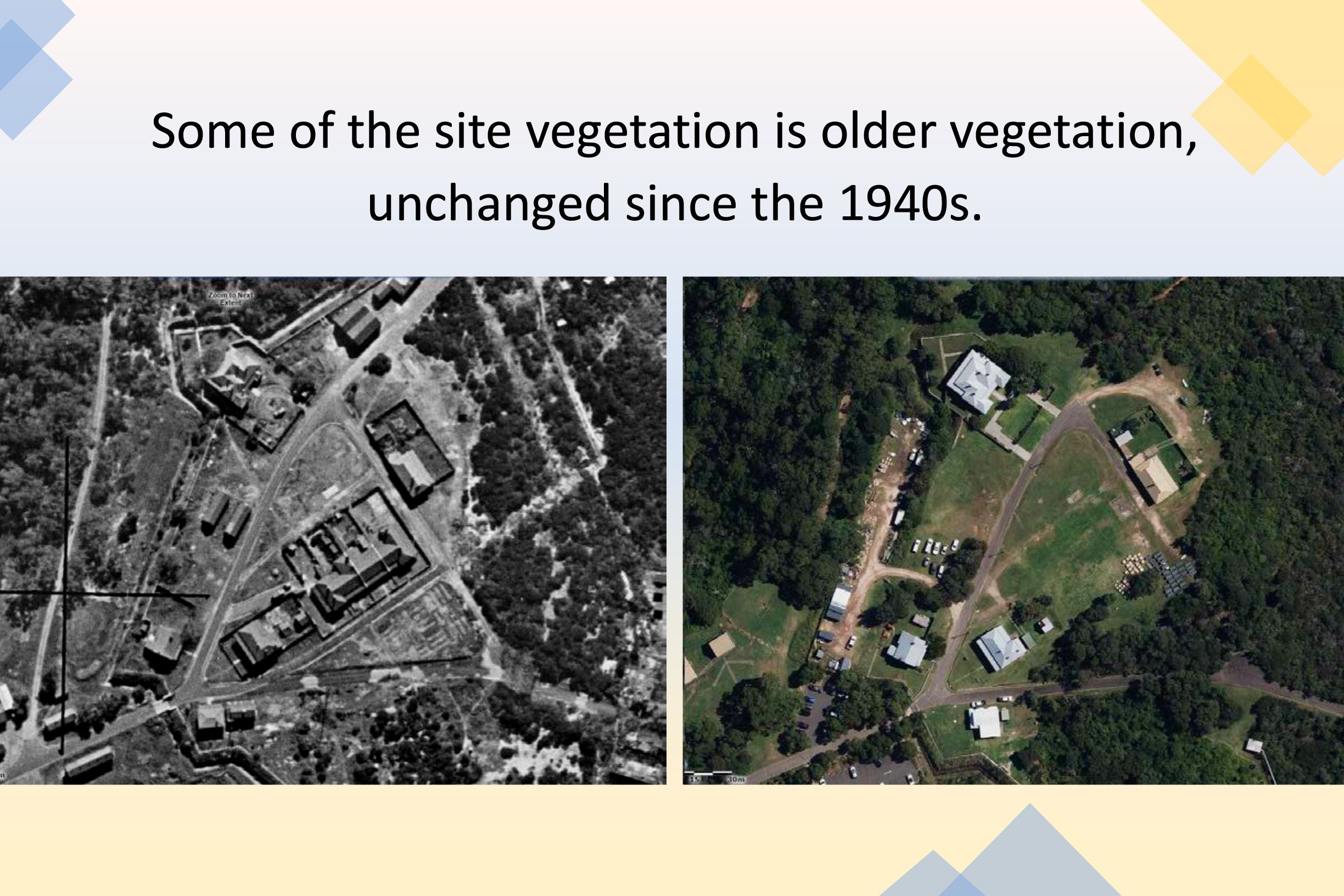

I've circled the area (ABOVE) that could be affected by this development. Just roughly speaking, the COLA would go into an area like this. And if you look at this little triangle of vegetation here you may have noticed that that was vegetation that appeared in some of the early photographs dating back to the 1930s.

Kate talked about the feedback that we got about this vegetation being really disturbed and said that it's not of great value. The vegetation there has been around in a relatively intact state since well before the 1930s, by the looks of things.

I'll talk more about the type of vegetation. Still, in looking at this aerial photograph, the only thing I want you to notice is that you've got an array of other buildings that are present on this historic site. Other buildings, tracks, and roads ramify out through the bushland of the National Park. So there's a lot of other scope for other considerations in the future if people start to opt for the easy way out of clearing bushland within the National Park.

This is a development that might have, in some people's eyes, a small environmental impact by removing some bushland, but it sets the scene for other things to happen in the future as Sydney grows. And there is a lot of pressure to look out for sites like this and other sites in the future.

Every different vegetation type in New South Wales has been classified and there's a database of information about it called BioNet. The vegetation in the area that we're looking at [Middle Head Fort], is a type of coastal heathland vegetation that typically develops on sandstone sites and relatively infertile soils. And you can see that a reasonable amount of it has been mapped on and around the National Park, and around the site

It's known as Sydney Coastal Foreshores Forest, a relatively low forest affected by coastal winds, salt spray, etc. Some threatened species are known within it. Some of those threatened species are plants that have been planted back into that community to reintroduce some threatened species' biodiversity into that area. There are also threatened animals that use that as a foraging habitat. If you overlay the development footprint of the building and the asset protection zone, you'll see a lot of this coastal sandstone vegetation has to be cleared around the building.

The other thing that I see immediately in looking at this site is that there are a lot of grassland areas as well that don't have vegetation constraints, but they do have historical constraints. When I started to put together this presentation tonight one of the things I ended up with was I realised that to properly criticise and evaluate what is being proposed there needs to be a thorough biodiversity assessment report.

A biodiversity assessment report is a requirement of the Biodiversity Conservation Act. I have been sent a copy of the report this afternoon. I haven't had a chance to look thoroughly through that report. A detailed report that covers this site, and it addresses some aspects of the legal requirements for assessment under the state legislation.

Broadly speaking, two types of environmental impacts can occur because of a development like this. The obvious development impact comes from the direct impacts of clearing native vegetation. The more subtle impacts are indirect impacts that come about from things like soil erosion and disturbance by people using the nearby site. They can also come about subtly by the increase in introduced animal presence, such as the black rats that we get in the city that prosper in environments where food and rubbish might be left. So, the indirect impacts of this development can go a lot further than those marks on a map.

The impacts need to be weighed up very carefully. People need to say, 'do you really want to risk some of this bushland that's been set aside in a national park specifically for conservation?'

I mentioned before the patch of bushland that we're talking about here. Comparing photographs (ABOVE), there are parts of that bushland that were present in the 1930s and 1940s. So it's been around for a long time. I do agree that the edges of that bushland have been disturbed by weeds. I also agree that it is solid bushland now, and it can easily be managed and remedied.

So, the first question that's been answered already this afternoon is that we need to review the biodiversity assessment report. We need to see what it covers in terms of legislation, and I've spoken about the Biodiversity and Conservation Act, and that's a necessity; in my quick reading of the report, though, one thing I didn't notice straight out was whether or not it covers the National Parks and Wildlife Act. To gazette a national park, you need to zone the land as a national park for conservation, so this land is zoned C1, so it has its own specific objectives for management. The flora and fauna impact assessment needs to evaluate what you're doing to the environment against the objectives of the national park and the, you know, the conservation zone objectives. There's Commonwealth legislation that provides a layer of protection too, and then there's also things like the Biosecurity Act which covers weeds and feral animals and the duty of care, some of the indirect impacts that you can have as well.

Looking at legislation is useful when you're considering impact. This slide (ABOVE) covers the National Park's objectives, and it comes from the National Parks and Wildlife Service Act of 1974. I've put some comments related to the objectives in the right-hand column. If you look at point number one, the purpose of reserving lands in National Parks is to identify, protect and conserve areas containing outstanding or representative ecosystems, natural or cultural features or landscapes or phenomena to provide opportunities for public appreciation, inspiration and sustainable visitor or tourist use and enjoyment, etc. Clearing an area of heathland doesn't achieve that aim, particularly when there are alternatives. Similar things are written down in some of the other objectives, but a national park is to be managed by the following principles: the conservation of biodiversity, the maintenance of eco system function, the protection of geological and geomorphological features and natural phenomena and the maintenance of natural landscapes etc. So again, clearing that site goes against the very basic requirements for national parks.

One of the other objectives that stood out, and it's very relevant to this proposal, is that it talks about the provision for sustainable use, including adaptive reuse of any buildings or structures. Modified natural areas having regard to the conservation of the National Park's natural and cultural values.

In conclusion, we need to review the biodiversity assessment report. To see how thoroughly the site has been investigated and what the authors have said about it. We need to see if the actual scope of the report provides an allowance for looking at alternatives that have a lesser environmental impact. This site has significant historical value and substantial biodiversity. It is also “inner city native vegetation”. Can we afford to allow vegetation like this in our national parks to be whittled away? Why should we? So, I ask the question, why clear bushland at all in a national park?

When alternatives are available, this is setting a precedent that could have ramifications for this national park and other national parks. Because if you can do it here, you can also do it elsewhere. There are some really important principles here. Coming back to the threatened species legislation, one of the dangers inherent in the Biodiversity Conservation Act, as it applies to this site, is that this is not an endangered forest type. Sandstone vegetation of this type is relatively widespread up and down the coast, but it's one of the communities set aside to be conserved by the National Park. There are threatened species values in this landscape, but it's not vital for threatened species, but it is an important part of the overall vegetation and landscape of the National Park.

I'll finish by saying that one of the things that I did notice when I read the report was that there's a constraints map that maps the constraints of the vegetation surrounding the site. The heathland is mapped as high-constrained vegetation. So the information that you've been told, if they did imply that it was a low constraint, is different from what the ecological report says. So, it deserves careful scrutiny.

– end transcript Dr David Roberstson –

Transcript: Kate Eccles, President Mosman Parks & Bushland Association

MPBA began life in 1964 when bushland was bulldozed for a road at Bradleys Head.

Public land, bushland and parks have continued to be our major concern. And, of course, many of our association members are bush regenerators.

Jill has given you a very complete picture of the proposed development at Middle Head and of Middle Head’s wonderful heritage significance. It remains for me to tell you a little about MPBA’s opposition to this proposal and our hopes that an alternative solution can be achieved.

Late in 2022, we were invited to respond to an Amendment to the SHNP PoM that would allow public land in a National Park to be used for a new building.

The proposal was for an Environment Education Centre at the Soldiers’ Institute on Middle Head. (MPBA members here will remember that that was where we held our Bush Regeneration Workshop last year).

An Environment Education Centre is a wonderful idea. Who would not want our children to learn about the environment?

The problem was that the Soldiers Institute was not big enough and a new building, a COLA (a Covered Outdoor Learning Area), would be needed.

And the problem with that was, as you’ve heard, new buildings aren’t allowed in the National Park at Middle Head.

The Plan of Management would have to be changed to allow a new building. A precedent would be set if the Plan of Management was changed for one new building. We could be asked to approve another amendment for another building.

That wasn’t the only problem. Jill will have left you in no doubt about the heritage values of Middle Head. In the area where the Soldiers Institute is, there is a cluster of similar buildings – similar in age, scale, and style. There is a Conservation Management Plan for this area, which says “The interrelationships between the buildings should not be obstructed by new structures. New structures would intrude on these relationships and break down the site’s interpretive value”.

There is yet another plan to consider (so many plans!)– the NPWS MH and Georges Head Masterplan, made in 2016. This is what we said about that plan. “A new building should only be contemplated if it is essential to the purposes of the park and where there is no alternative”.

THE ALTERNATIVE

There is an alternative. Ten Terminal, just down the road, has empty buildings …..not NEW buildings. Buildings waiting to be used.

So, then we wrote to various government Ministers.

THE PROBLEM

The problem here is that NPWS and the NSW Education Department are in the jurisdiction of NSW.

Ten Terminal down the road is the jurisdiction of the Harbour Trust and the Commonwealth Government.

That is the hurdle we have to overcome.

We wrote to the Minister for the Environment NSW and the Minister for the Environment (Commonwealth)

And we wrote to the Minister for Education NSW.

THE RESULT

Well, that did result in a visit by the NSW Education Department to the Commonwealth Harbour Trust Ten Terminal buildings.

The Information Evening

Then came the NSW Schools Infrastructure Information Evening about the proposal and the preferred COLA site location. On December 6, 2023 (We love a close-to-end-of-year consultation like that!)

Both HPG and MPBA were devastated. It was worse than we expected, and the Harbour Trust option would only be considered after the option of the NPWS Soldiers’ Institute location was completed.

LAST BUT NOT LEAST - THE CLEARING OF BUSHLAND

Here is another reason for not allowing the new building (the COLA) to go ahead in the National Park

ABOVE: Kate Eccles (L) and Julie Goodsir inspecting bushland that will be destroyed if the COLA is allowed to proceed.

A new building in a natural area with bushland must be protected from bushfire.

The Bushfire Assessment Report indicated that the new building (the COLA) would need an Asset Protection Zone and require bushland to be cleared.

MPBA holds, as a matter of principle, that “No bushland, however degraded, should ever be destroyed”.

At the Information evening, attendees heard that the bushland was degraded and had little value.

We dispute this. Even a casual visit will show Banksias, Kunzia, Grevilleas, and Glochidion (cheese tree) growing healthily, with few weeds except at the edge.

And it is bushland that has been here, probably forever. You can see it in the photos from the 1930s and 1940s of the subject site.

– end transcript Kate Eccles –